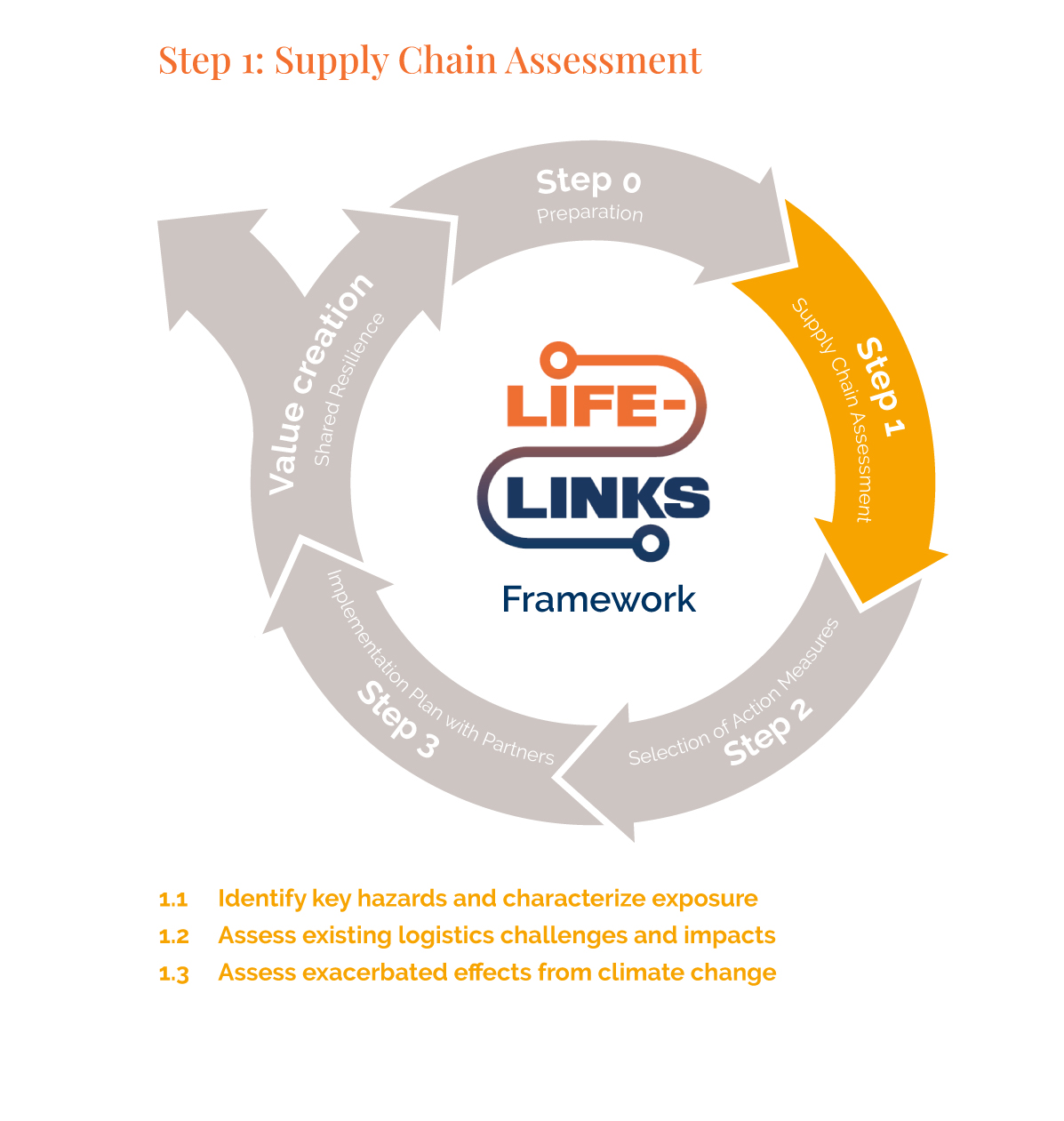

Part C. Life-Links Steps

Step 1: Supply Chain Assessment

Outcome: determined which and how supply chain stakeholders are impacted by disruptions of critical transport links exacerbated by climate change.

Introduction: Pragmatic approach

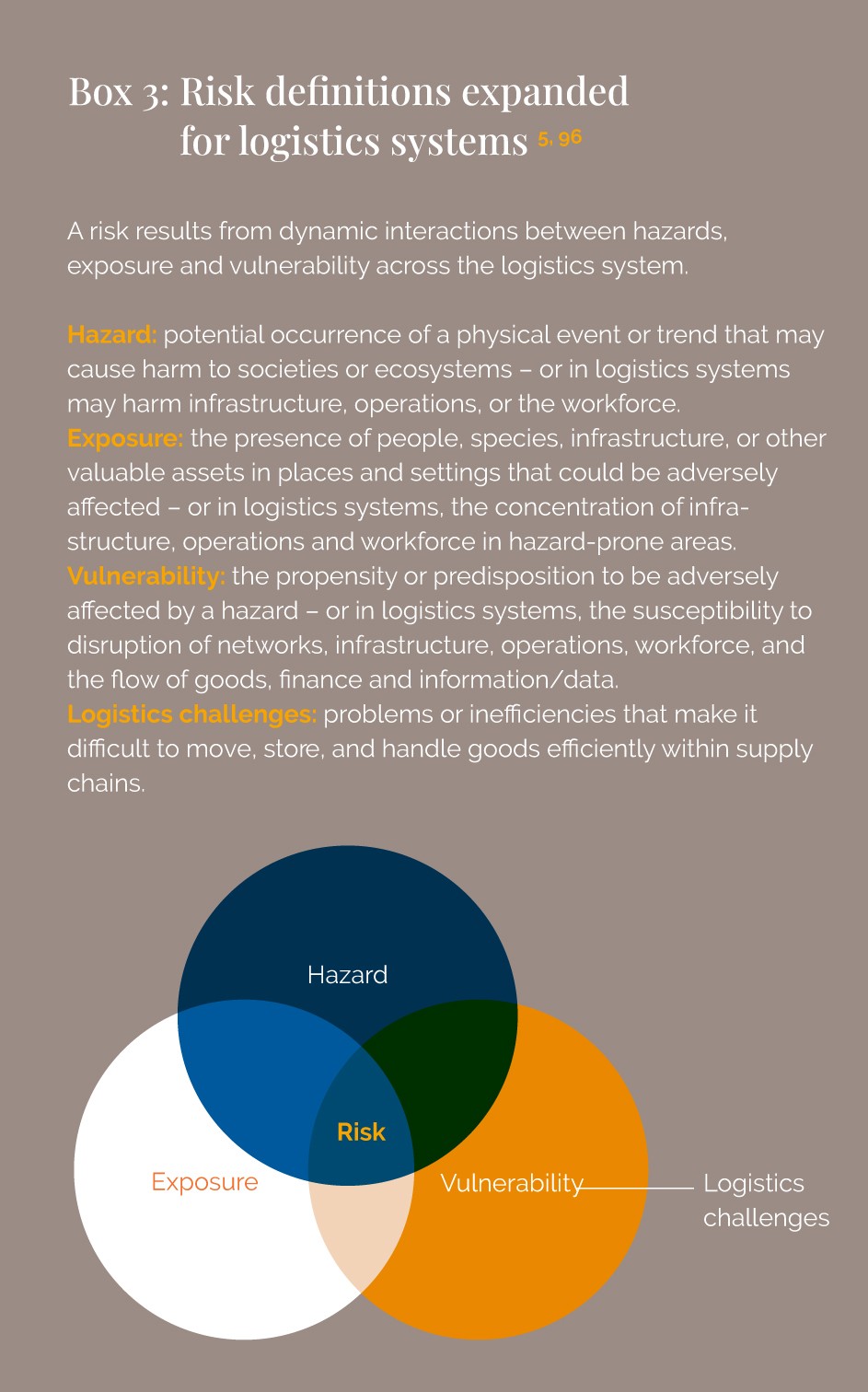

Risks result from the interaction between hazards, exposure and vulnerability (see Box 3). An assessment of risks and impacts of supply chain disruptions can be carried out in different ways, from qualitative to quantitative, and at varying levels of depth. The choice depends on the time, resources, and data available, which will naturally differ from one application to another.

If a decision is made to carry out a comprehensive climate risk assessment (CRA), then there are multiple guidelines available (see Resource). In addition, the FAIR data guiding principles can support the assessment of supply chain risks and impacts, especially when data is obtained and integrated from multiple sets and sources and combined with AI.

Resource: Overview of Guidelines and Tools

Resource: Overview of Guidelines and Tools Resource: Fair Guiding Principles on Data

Resource: Fair Guiding Principles on DataThe supply chain assessment approach described here is pragmatic, working within the limits of time, resources, and data. The is done by:

- Taking a bottom-up perspective, starting with conversations with stakeholders, and it stays focused on the supply chain, looking closely at the challenges that disrupt logistics and drive up costs.

- Prioritizing to make it evident that costs and other impacts will rise in the future due to increasing climate change. Companies and other stakeholders are far more likely to invest in solutions when they already see the price of today’s logistics challenges and resulting disruptions.

- Making results relevant to stakeholders as gaining their support for collaborative actions to build resilience is essential. If stakeholders cannot see themselves in the picture, or fail to grasp the projected negative impacts of climate change on their supply chain, securing their buy-in becomes a major challenge.

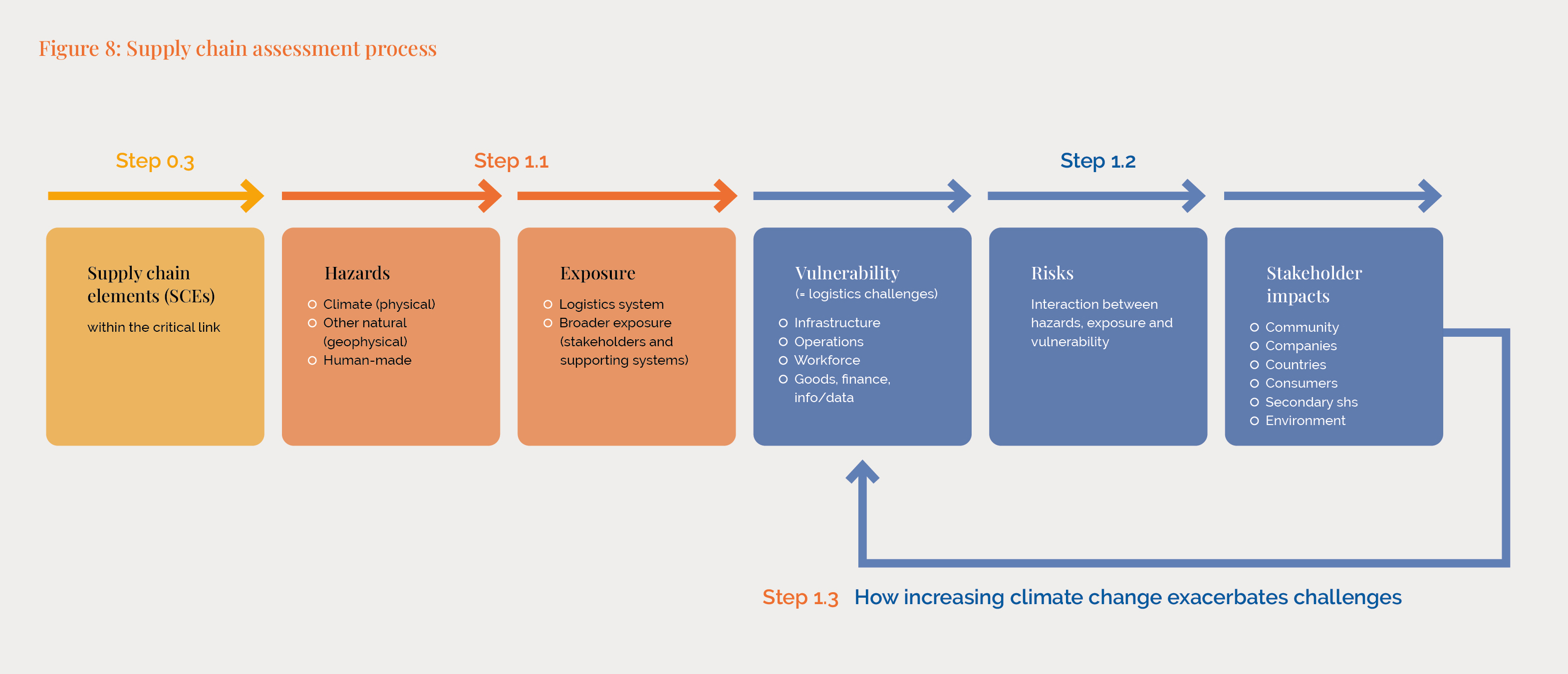

This step begins with a qualitative identification of key hazards to the critical link and a characterization of exposure, looking beyond climate hazards and the logistics system to place the assessment in a broader context. (sub-step 1.1). This is followed by a vulnerability assessment focused on existing logistics challenges, and the resulting disruption risks and impacts (sub-step 1.2). Then it is assessed how climate change will make today’s logistics vulnerabilities even worse (sub-step 1.3). For example, the lack of refrigeration generates food waste, and higher temperatures exacerbate this problem.

1.1 Identify hazards and characterize exposure

Begin with a qualitative determination of hazards and exposure to supply chain disruptions, extending beyond climate change. This ensures the assessment remains relevant to stakeholders, especially companies with broader supply chain risk management approaches.

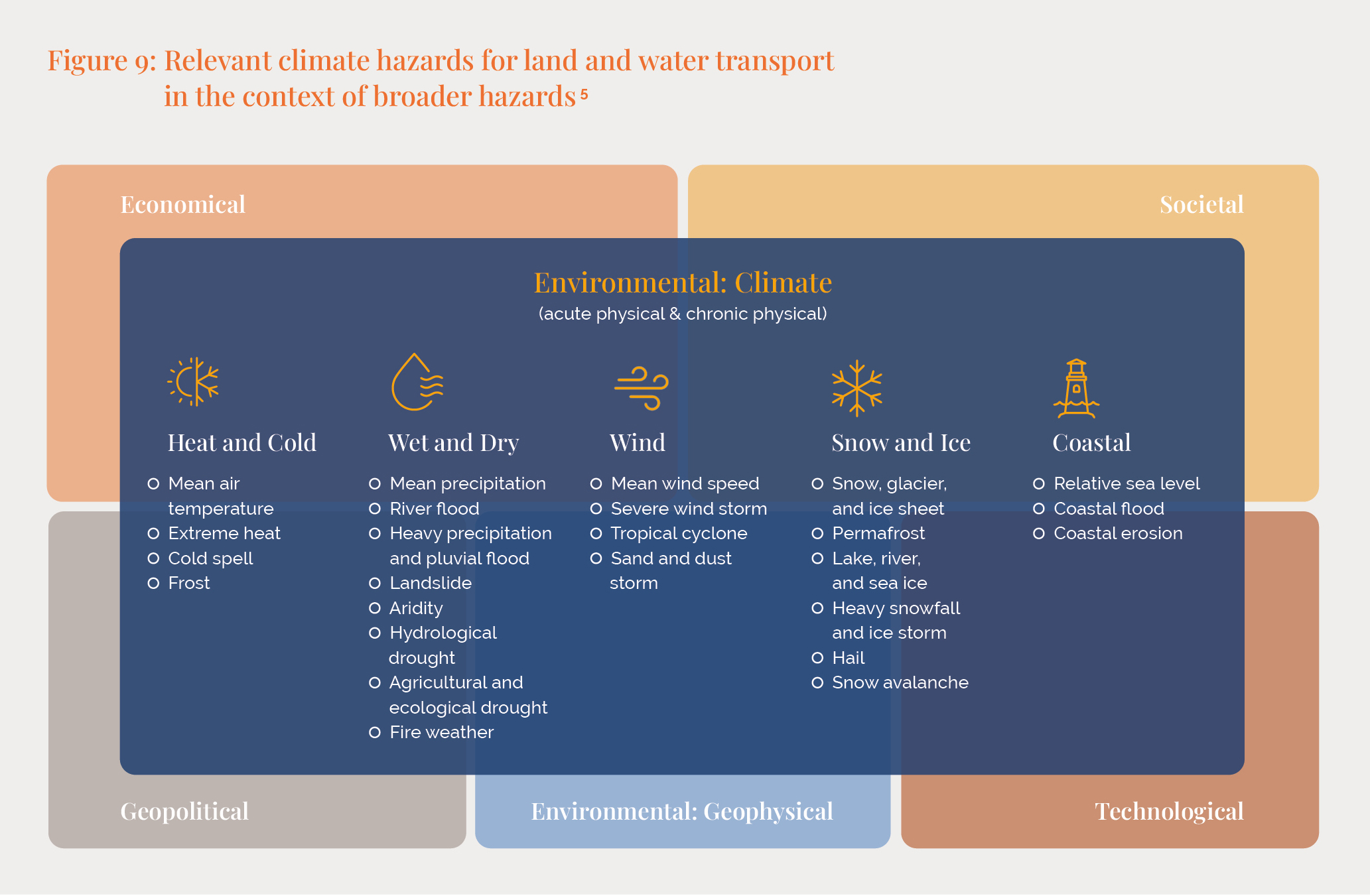

a. List relevant climate and other hazards

Start by listing the climate hazards that currently apply to the transport/logistics SCEs that make up your critical link. For example, sea-level rise applies to a port but not to a packhouse located inland, whereas storms apply to both. List relevant other hazards, such as earthquakes, political instability or a conflict. These may be important for the willingness to invest in strengthening the critical link within the existing supply chain, as many companies are rethinking their entire supply chain network.

Resource: Hazards to Supply Chains and Logistics

Resource: Hazards to Supply Chains and Logistics

b. Characterize the logistics system exposure

Explain the exposure of the critical link SCEs including:

- Network (the spatial configuration of nodes, modes and hubs, and which the critical link is part of).

- Infrastructure or physical assets (transport infrastructure, logistics hubs, vehicles, equipment).

- Operations (management processes, systems, and governance structures).

- Workforce (own workforce, contractors, suppliers).

- Flow of goods, supported by related flows of finance and information/data.

c. Characterize the broader exposure

Characterize the broader exposure, which refers to the dependence of stakeholders (companies, countries, communities, consumers and secondary stakeholders) on logistics flows, making them vulnerable to disruption even beyond the logistics system itself. For example, local communities living near a port are also exposed to storms or strikes that shut a port down. This also includes supporting systems (societal, legal, financial, physical, nature-based).

Resource: Logistics System and Supporting Systems

Resource: Logistics System and Supporting Systems

1.2 Assess logistics vulnerabilities, risks and impacts

Once broad hazards and exposure have been determined, the next step is to zoom into the logistics system to assess vulnerabilities and identify risks and impacts.

One approach is to assess the vulnerability of transport modes and logistics hubs that make up the critical link, as show in Table 3. For example, an unpaved road or one lacking drainage is more vulnerable, and poor maintenance further increases the risk. However, developing vulnerability relationships based on hazard intensity and exposure characteristics is challenging and often requires detailed site-specific information, which is frequently lacking.

A pragmatic solution is to use existing logistics challenges as the entry point. Logistics challenges are the problems or inefficiencies that make it difficult to move, store, and handle goods efficiently through a supply chain. They can relate to infrastructure (e.g. unpaved roads, limited cold storage, inadequate vehicles), operations (e.g. inefficient collection, long lead times, packhouse bottlenecks), workforce (e.g. limited skills, long work hours, exposure to heat stress), flows (e.g. perishable goods with short shelf-life, broken cold chains, payment delays, data errors), or the external environment (e.g. certification requirements, customs procedures, market standards).

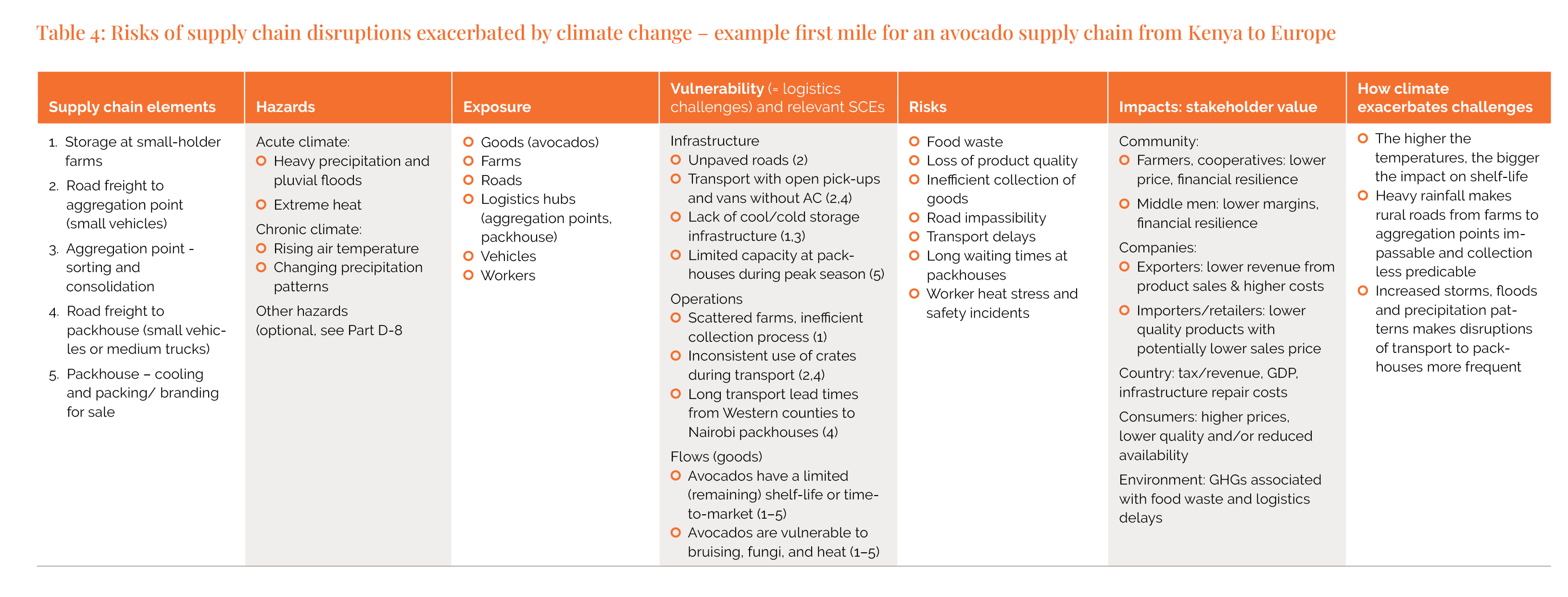

Focusing on logistics challenges makes vulnerabilities more tangible and enables an easier connection to risks and impacts that stakeholders can clearly recognize. It also helps them understand how climate change may exacerbate existing challenges. This is illustrated with the avocado application in Table 4.

a. Understand logistics challenges

Begin with the supply chain elements that make up your critical link as defined in Step 0. For these elements, identify the existing logistics challenges that affect the flow of goods transportation through the supply chain. The most effective approach is to first consult stakeholders who have a direct role in the supply chain – such as farmers, cooperatives, shippers, logistics service providers (LSPs), associations, or non-governmental organizations (NGOs) – to understand the day-to-day challenges they face. This ensures that the type of goods being transported, as well as its stakeholders, are implicitly considered, both of which are key determinants of the impacts of transport disruptions (and subsequently the value created by addressing them). These stakeholders are also more likely to know what possible solutions exist or have been attempted, with whom, and may later support the implementation of action measures.

It is important to note that only a combination of stakeholder perspectives can provide a true understanding of the underlying reasons behind certain challenges. These extend from the field to the final consumer. For example, a trader may describe delays at the first mile that affect the shelf life of avocados, while a European importer may add that inconsistent quality is exacerbated by different batches of avocados with varying remaining shelf lives being loaded into one container.

b. Connect logistics challenges with risks

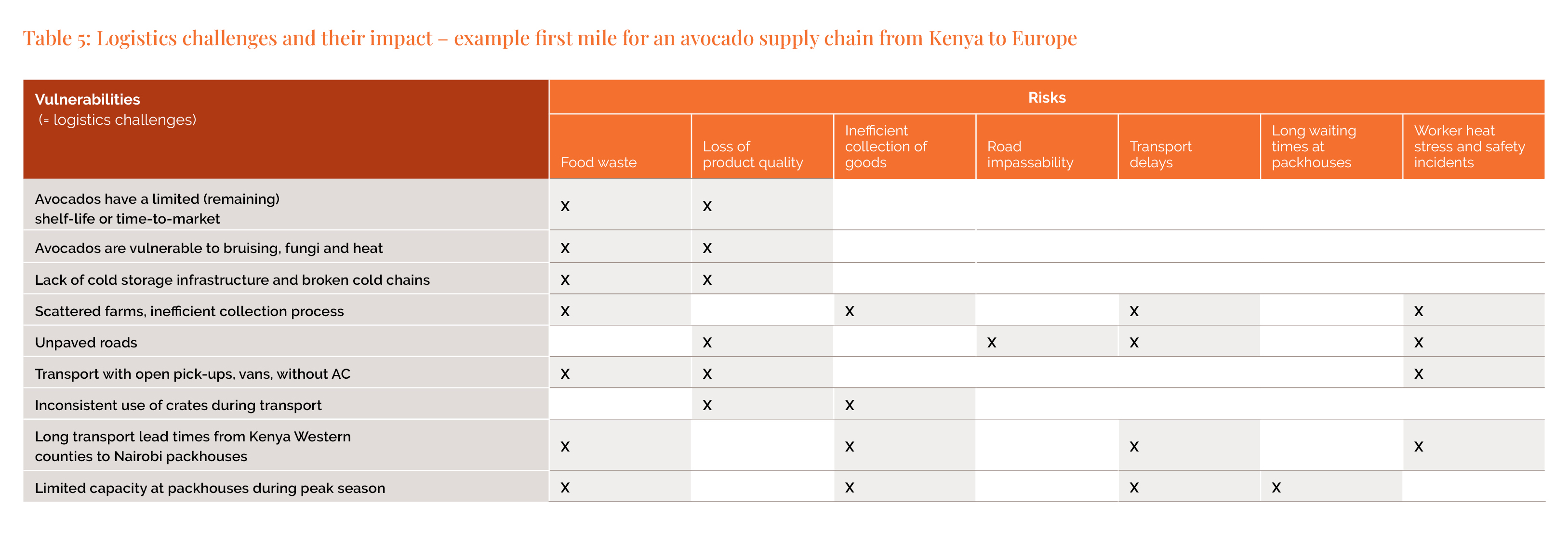

Next, determine how these logistics challenges can lead to risks of disruption. For example, as shown in Table 5, unpaved roads are more susceptible to heavy rain and flooding, which can make roads impassable or delay transportation. Inconsistent use of crates may lead to bruising of avocados transported in open pick-up trucks along these roads. Since logistics challenges often connect to multiple risks, use a matrix to record and analyse these relationships.

Reference:5

Reference:5

c. Determine impacts for stakeholders

Make the connection between the risks from disruptions and the potential impacts on stakeholders – communities, companies, countries and consumers – especially on the (socio-)economic value that these supply chains bring. For example, farmers may get less income from avocados, while importers and retailers are faced with lower product volumes or quality, which may affect the price they can charge consumers. For example, household loss as % of income (due to increase in transport costs and due to shortages).7 An expanded impact analysis could also include secondary stakeholders, such as insurers facing increased claims resulting from infrastructure failures.

The “environment” and future generations that depend on this, should be treated as a distinct stakeholder. For example, if avocados are discarded, the resulting food waste generates GHG emissions, which may need to be accounted for by companies sourcing avocados from this supply chain.

Where possible, validate assumptions about how disruptions affect stakeholder value. This is critical for building cooperation on future solutions. For example, if most of the costs associated with losses are currently borne by farmers and first‑mile operators, importers and retailers may not yet feel sufficient financial impact to do anything about it. Try to show if this could change over time, as has already been observed in coffee and cocoa supply chains due to climate change, reduced interest to become a coffee farmer, and other reasons.

Resource: Examples of Metrics and Indicators

Resource: Examples of Metrics and Indicators

When assessing impacts on communities, it is essential to take a holistic view of their livelihoods, as these are ultimately what we aim to protect. Sustainable livelihoods are commonly defined through five types of capital that people draw upon to achieve their livelihood objectives, and which can be impacted by disruptions: 102

- Physical capital: basic infrastructure (e.g., transport, shelter, water supply, energy, communications) and producer goods (e.g., tools, machinery).

- Financial capital: financial resources available to people, including stocks (e.g., savings, livestock) and regular inflows (e.g., remittances), which can support both consumption and production.

- Social capital: the social resources people can access (e.g., networks, connections, memberships, and relationships of trust, reciprocity, and exchange).

- Natural capital: natural resource stocks (e.g., land, water, forests, biodiversity) and the associated flows and services they provide (e.g., nutrient cycling, erosion protection).

- Human capital: the skills, knowledge, health, and capacity for labor that enable people to make use of the other four forms of capital.

1.3 Assess exacerbating effects from climate change

Finally, go back to revisiting the identified logistics challenges with a climate lens. The purpose is to understand how climate change could worsen current bottlenecks, create new hazards, or trigger complex chains of disruption across the logistics system. By looking at both direct and indirect impacts, this assessment helps ensure that resilience measures address not only today’s challenges but also tomorrow’s risks.

a. Describe how climate change exacerbates logistics challenges

Revisit your identified logistics challenges and assess whether climate change is likely to make them worse. For example, a road or railway that is currently only occasionally impassable due to rain may, with more frequent and severe rainfall, face regular disruptions. This could reduce profit margins for farmers, producers, or transporters to unsustainable levels or lead customers to stop ordering products due to higher prices.

b. Check for possible new future climate hazards

Also check for hazards that may emerge in the future. For example, a port that has not yet experienced flooding or extreme heat days may begin facing these risks within the next decade. Here is where risk assessment and climate modelling tools can come in handy to determine the extent of the risks (based on likelihood and severity) today and in the future. For example, a study of Brazilian coastal public ports made use of a risk index to classify risks from 1 (very low) to 5 (very high) for strong winds, storms and sea level rise.72 It is noted that most of these tools still lack the spatial granularity to assess at the level of a supply chain element.

c. Identify compounding risks and cascading effects

Identify where multiple climate-related hazards may overlap or interact with existing logistics challenges. For example, prolonged drought may simultaneously reduce crop yields and restrict inland waterway transport, or heat waves may coincide with energy shortages that disrupt cold storage and refrigerated transport. Such interactions can create “knock-on” effects across the supply chain, multiplying risks beyond those of individual hazards.