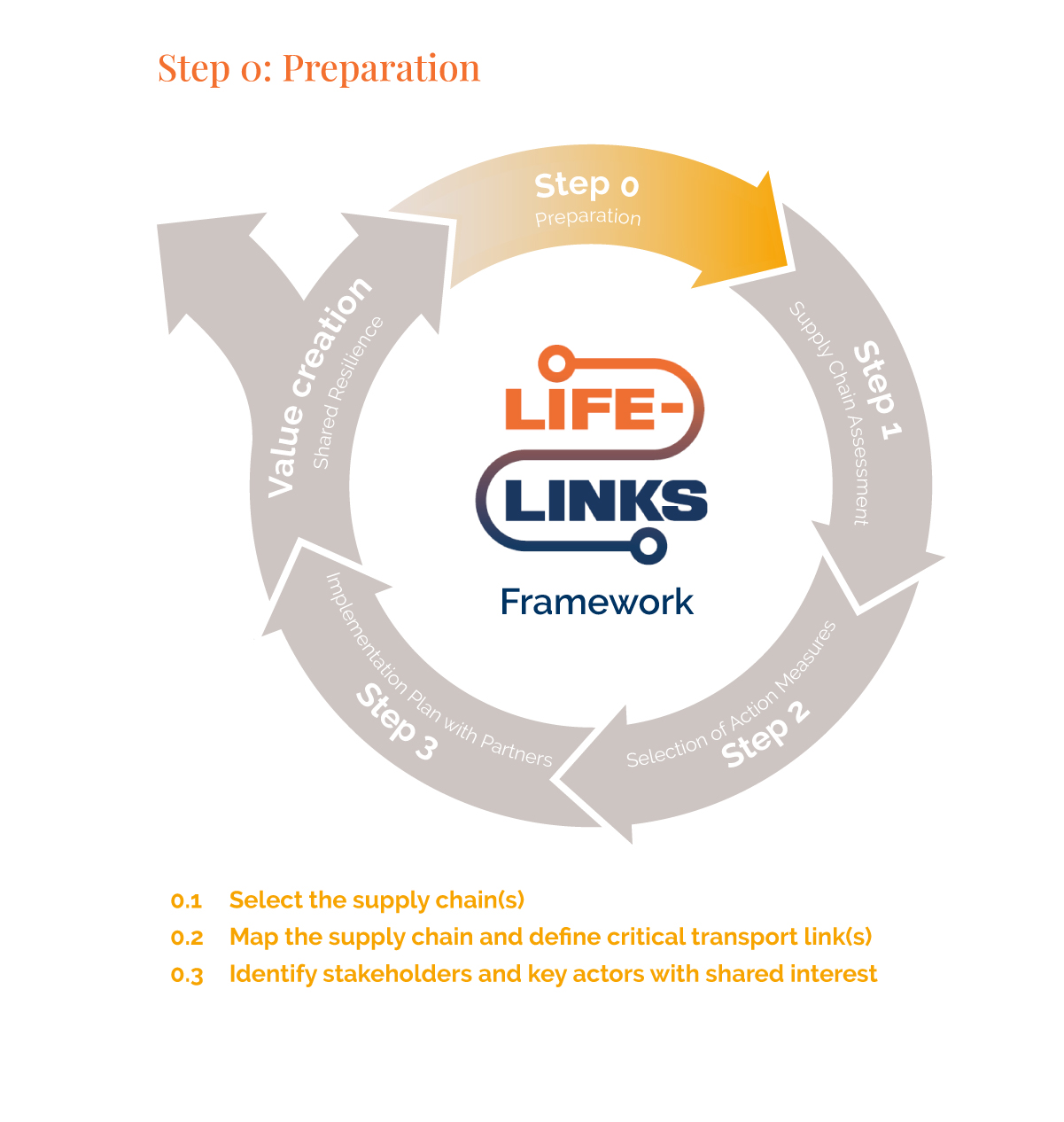

Part C. Life-Links Steps

Step 0: Preparation

Outcome: identified supply chain(s), critical transport link(s), stakeholders and key actors with shared interest

The preparation phase is about selecting specific transport links within end-to-end supply chains. This allows greater focus on vulnerable links, ideally with high GHG reduction potential, and helps involve a broad range of stakeholders and actors. It can also serve as a continuation of the cycle after partners successfully implemented measures to improve resilience and sustainability.

0.1 Select the supply chain(s)

The process for selecting the supply chain for the Life-Links application is described below and illustrated with fictive examples in Box 2.

a. Clarify motivations as initiating actor

Clarify the motivation of the initiating actor of the Life-Links application, which may be one or several supply chain actors, such as companies, government agencies, foundations, insurers, or others. The motivation to pursue supply chain resilience is a key factor influencing the choice and scope of the supply chain. For example, a manufacturer’s primary motivation may be to secure continued access to critical materials, a retailer may prioritize the sourcing of coffee, cocoa, or avocados that have sharply increased in price, while a foundation may focus on protecting the livelihoods of local communities.

b. Consider other factors

Consider additional factors when selecting a supply chain, such as

- Vulnerabilities and past disruptions with significant impacts.

- The type of goods, trade volumes, and economic value, while avoiding products that are environmentally or politically too sensitive.

- The dependence of local communities for their livelihoods.

- Exposure to regulatory requirements that are connected to supply chain visibility.

- Opportunities to leverage other developments, such as existing emissions accounting and decarbonization plans, initiatives and investments by other actors, and favourable policy environments.

For some stakeholders, the choice of supply chain is straightforward. For example, it is easier to select a supply chain involving a single material, commodity, or finished good. For others, the process may require a more detailed preliminary assessment, particularly for multinational companies with thousands of multi-tier supply chains. In such cases, guidance may be needed to identify the most vital or promising supply chains, since not all can be subjected to the same level of scrutiny.

c. Decide on the supply chain scope

Decide on the supply chain scope by giving clarity on both the goods or products as well as the origin and destination. For example, a cocoa supply chain from Ghana in West Africa to Europe via the Port of Rotterdam. Supply chains within a country or continent could also be selected, for example, the wine supply chain from vineyards in Bordeaux, France to supermarkets in Germany, or the aerospace supply chain from Boeing’s aircraft assembly plants in Washington to airlines operating out of Atlanta, Georgia.

Case Study: Fictive examples of supply chain selections

Case Study: Fictive examples of supply chain selections

0.2 Map the supply chain and define critical link(s)

a. Map the supply chain

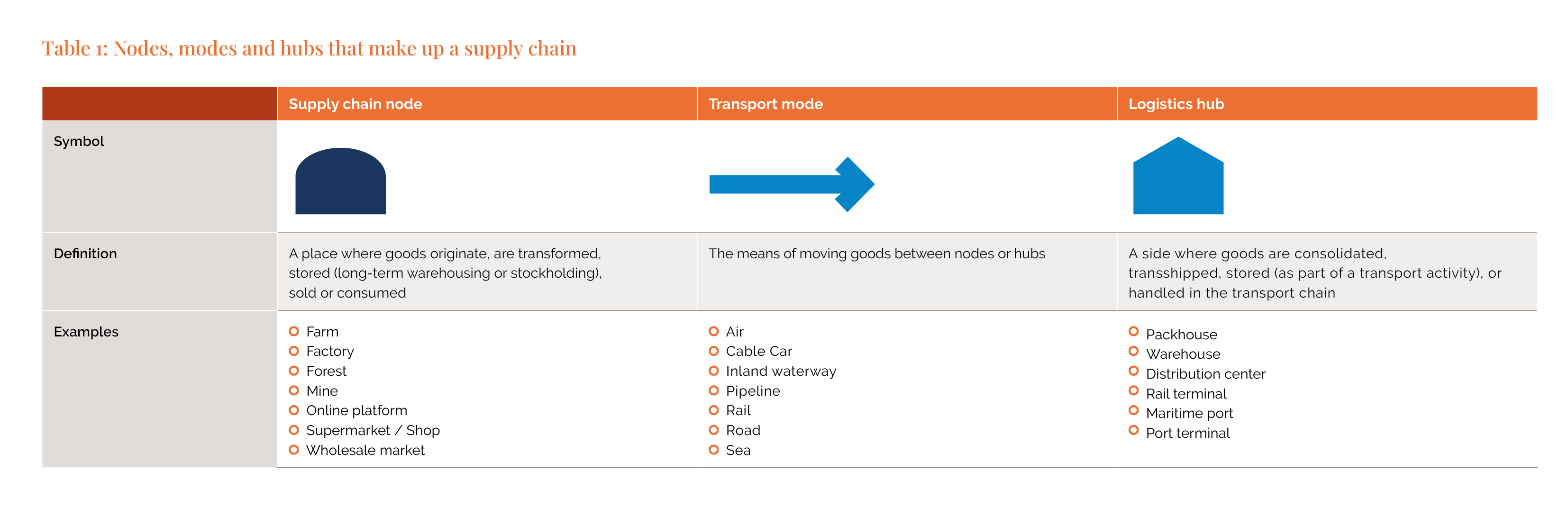

Map the chosen supply chain from origins to destinations, including supply chain nodes, transport modes and logistics hubs. As Life-Links focuses on transport and logistics, consistency with the GLEC Framework V3.1 and ISO 14083 is important, with further details on logistics hub types available from Fraunhofer.61 62 63

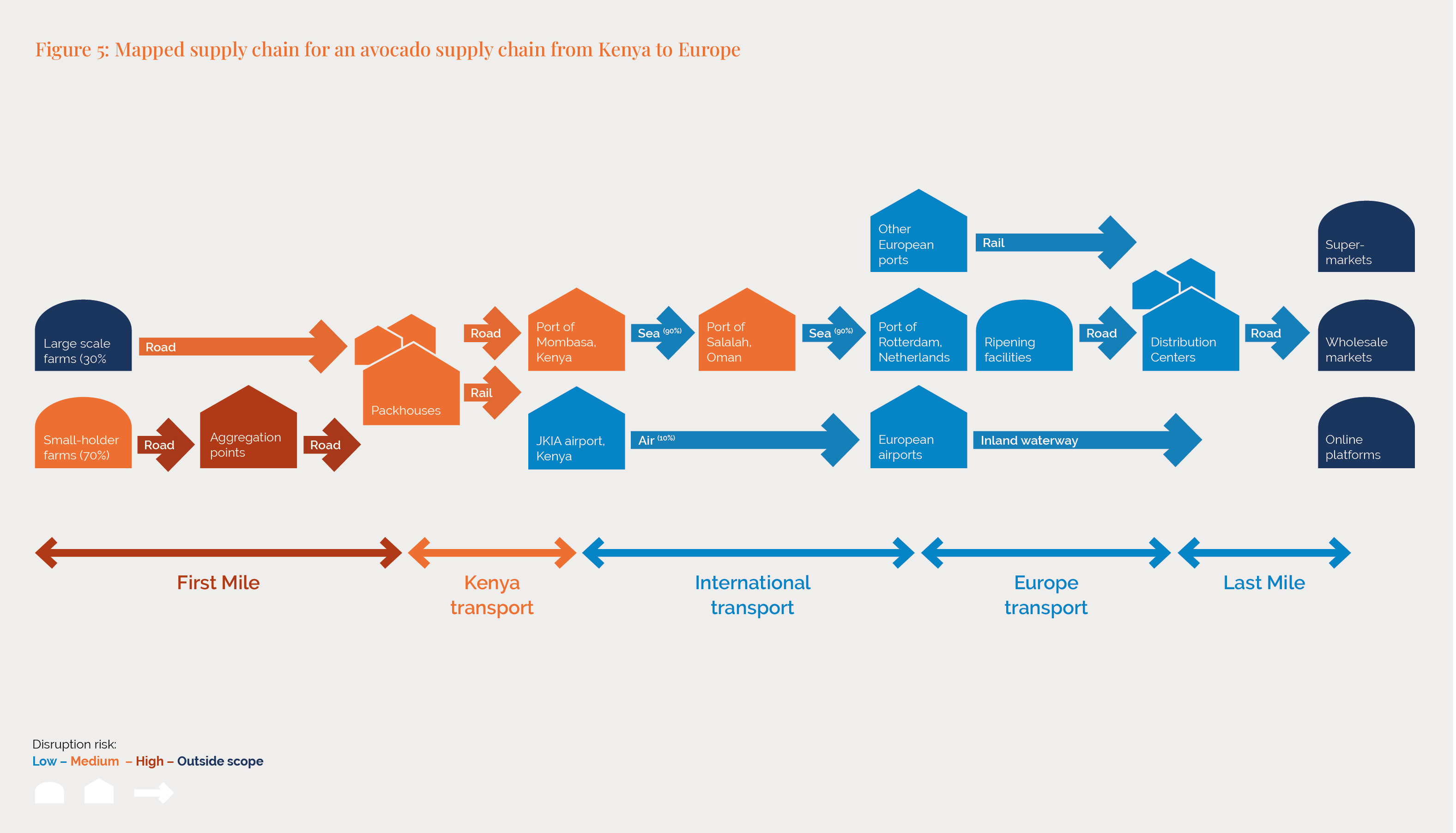

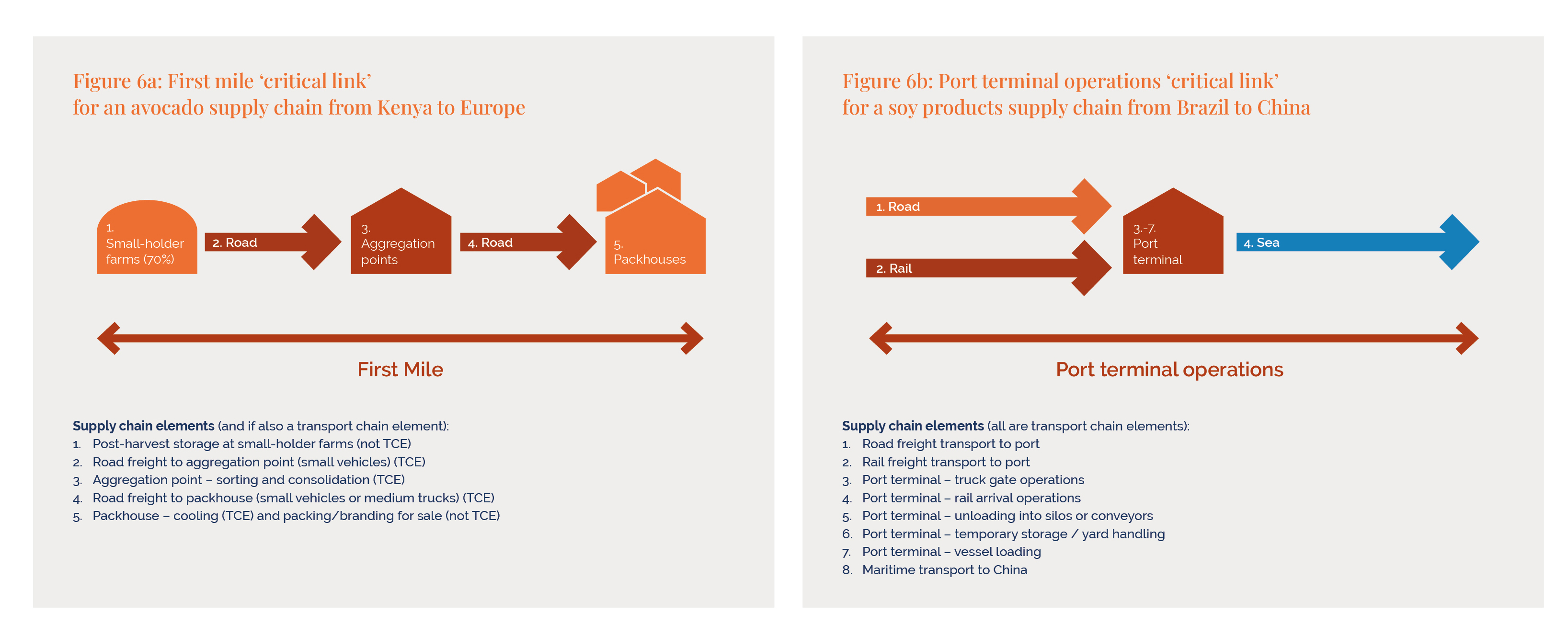

Where possible, use supply chain management tools to produce detailed maps. A practical, less resource-intensive approach is to begin with a simplified map and develop details only for the critical transport link selected later, for example, for an avocado supply chain as shown below. It is also useful to define segments as first mile, middle mile (potentially multiple in global supply chains), and last mile. Apply color-coding to qualitatively indicate disruption risk as low, medium or high.

b. Select critical transport or logistics link(s)

A transport or logistics link is a transport segment of the logistics network that connects two points. It always includes at least one transport mode, and may also include a supply chain node or logistics hub when these are part of the same connection. For example, include a road corridor, a port with its inbound and outbound road and sea connections, or the first mile from farm to packhouse.

A ‘critical link’ is a logistics link in a supply chain that is at risk of disruption, with the risk exacerbated by climate change, and whose failure would have significant impacts on stakeholders whose prosperity depends on the supply chain. The choice for a critical link should not consider the transport or logistics system in isolation, but rather in the context of its importance to the supply chain – specifically, the type of goods being transported and their value to key actors and stakeholders.

Some examples of a critical link selection from a supply chain perspective, with consideration of GHG emissions reduction potential, are:

-

Existing logistics vulnerabilities. For example, the first mile of Kenya’s avocado supply chain from smallholder farms to packhouses is a critical link because losses can reach 40% mainly due to logistics issues (storage, transport, packing). Rural areas often drive production, but weak logistics – marked by poor roads, aging fleets, informality, and weak regulation – lead to high transport costs, spoilage, losses, and food shortages. From a development perspective, the first mile is also a critical link because smallholder farmers, first-mile transporters (often informal or “popular” transport 144), cooperatives and their communities are the ones whose livelihoods are most affected by disruptions. Reducing food losses here also cuts a hidden source of GHG emissions in agriculture.

-

High volume or value of goods and costs. For example, the Port of Durban is Africa’s biggest port, handles over 60% of South Africa’s containerized cargo. It is also vulnerable to climate change and equipment breakdowns, resulting in berthing delays and reduced handling capacity in 2023 and 2024 and contributing to unreliable services and higher costs.64, 65 This directly impacts the profitability of maritime carriers and exporting companies and ultimately the country’s economy. The vulnerability of global container shipping to wider risks adds to the importance of port resilience.66 Reducing port congestion also lowers emissions from idling ships and trucks.

-

Seasonal vulnerability. For example, the 50-mile Georgetown-Vail stretch of the I-70 corridor through Colorado’s Rocky Mountains in the United States is a critical link because avalanches and heavy snow regularly close the road, leaving few alternatives.67 It is a major freight route between the Midwest and Western States and also supplies mountain tourism towns. Closures disrupt both interstate trade and local communities who depend on the corridor for jobs, services, and daily essentials.68 Avoiding detours and idling during closures also reduces fuel use and emissions.

-

Lack of alternative routes. For example, Laos PDR’s road segment in the North-South Economic Corridor between China and Southeast Asia is a critical link for agricultural and manufacturing supply chains. Alternative routes are scarce, railway infrastructure is limited, there are no seaports, and its road infrastructure is highly susceptible to climate hazards.69 Disruptions are most felt most acutely by Lao communities, companies and the country’s economy. Investments that improve efficiency can also reduce freight emissions over time.

-

Regional economic life. For example, the Gotthard Pass region in Switzerland is a critical link because tunnels and roads there carry large volumes of north– south European trade. The same routes also supply Alpine communities with food, fuel, and household essentials. Limited alternatives for crossing the Alps mean disruptions directly affect both European trade and local livelihoods.70 Protecting this corridor also safeguards Europe’s shift from road to lower-emission rail freight.

-

Overlap between supply chains for consumers and buyers. For example, Tanzania’s transport routes for agricultural, processed food and manufactured products consumed by households show significant overlap with international buyers purchasing goods from or passing through Tanzania. Two segments of trunk roads of 181 km combined were selected as critical links based on the goods passing through and the impacts from disruption.71 Upgrading these trunk roads reduces congestion, cutting costs and emissions for multiple supply chains.

c. Define supply chain elements within the critical link

Take the supply chain map as a starting point to define supply chain elements for the critical link. A supply chain element (SCE) is the smallest building block in a supply chain, that ideally spans no more than

- One activity at a node.

- One transport mode movement between two points.

- One activity at a logistics hub.

When a supply chain element involves a transport or handling activity, it is also considered a Transport Chain Element (TCE) under ISO 14083 / GLEC Framework. Depending on the desired level of detail, record descriptive attributes where applicable (e.g., port name or code, vehicle type, geographic locations of roads, facility type, assets used, and operating requirements such as bulk vs. liquid, temperature-controlled, or containerized).

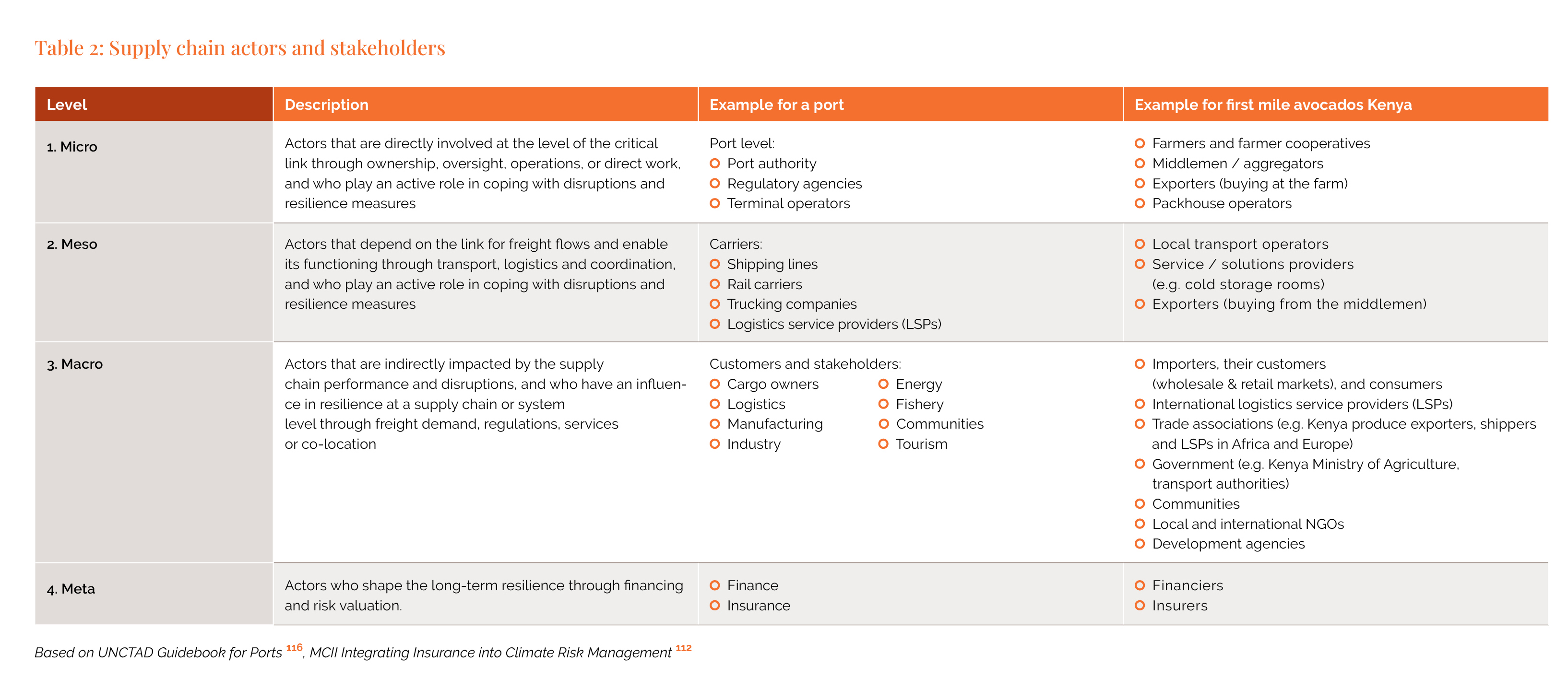

0.3 Identify stakeholders and key actors with shared interest

a. List the type of stakeholders and actors

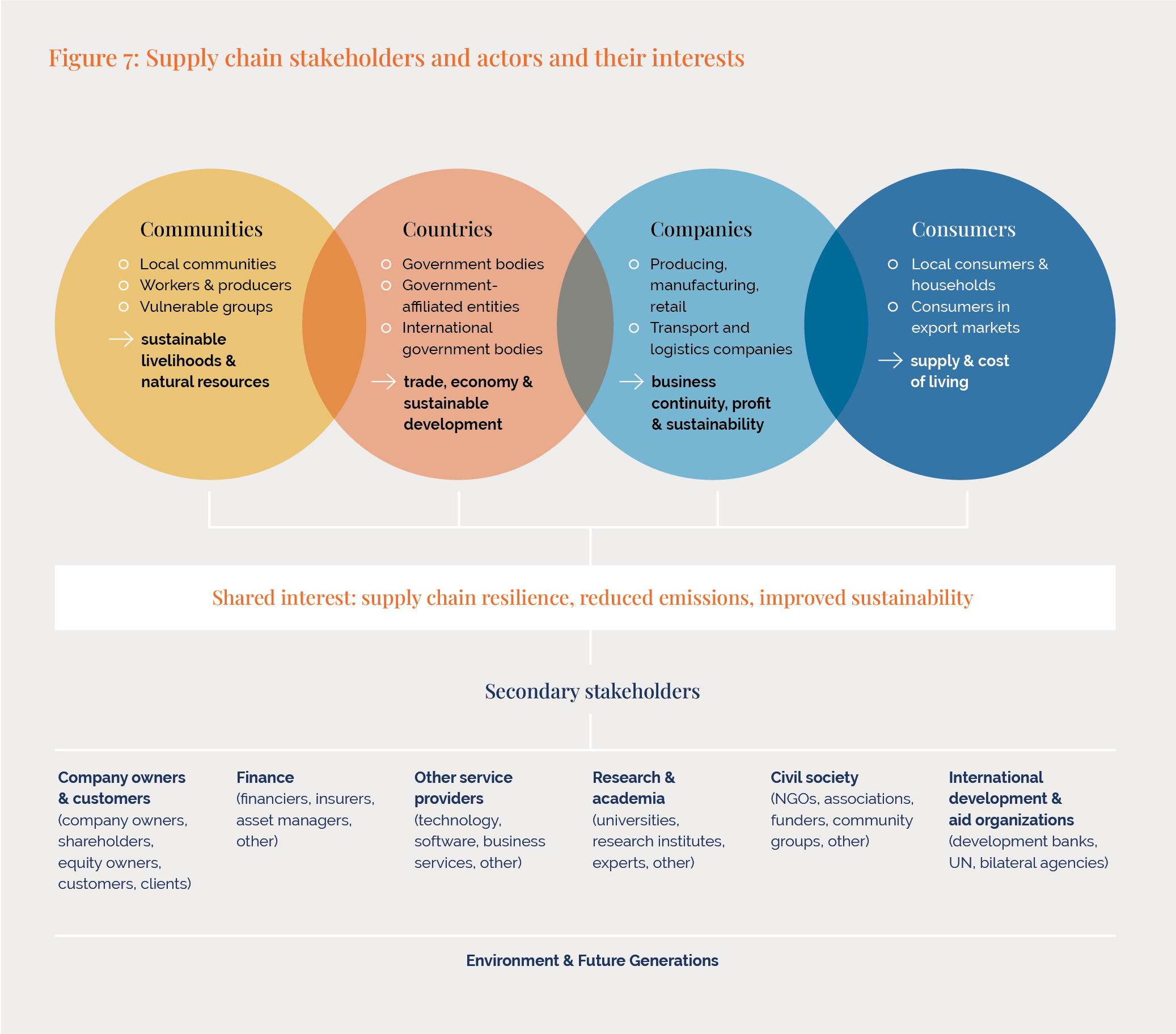

List which type of stakeholders and actors are relevant to the supply chain. In the context of Life-Links a stakeholder has an interest in, can influence, or are affected by the outcome of the project, whereas actors may actively participate in the project and in making decisions. Primary stakeholders are communities, countries, companies and consumers, whereas secondary stakeholders work with, for, on behalf of primary stakeholders. The below figure and the separate list of stakeoholders and actors can be used as a starting point, including alignment with the structure that EU directives (CSRD and CSDDD) expect companies to use when identifying stakeholders.

Resource: List of Stakeholders and Actors

Resource: List of Stakeholders and Actors

b. Categorize stakeholders and actors

Next, categorize and prioritize your stakeholders based on the critical link and the full supply chain. This should be done in a way that shows different levels of influence on the resilience of supply chains, while at the same time allowing for practical stakeholder engagement that is necessary for taking action.

c. Identify key actors with shared interest and potential partners

Finally, identify the key actors you will likely need to approach early and actively engage for the project to succeed. As part of this, determine their motivations and whether there is a shared interest in keeping the supply chain functioning. If key actors join as project partners, steps 1 to 3 can be carried out jointly, resulting in a shared implementation plan of feasible actions.

For example, if soybeans are selected as a supply chain going through the Port of Santos to export markets in China, then Chinese state-owned trading firms, feed manufacturers and processors are likely key actors. Will port resilience matter (enough) to them and are there transport links connected to the port that should be considered? In some cases the initiator of the project may wish to involve a trusted third party acting transparently to oversee the steps and manage the power imbalances along supply chains that often hinder cooperation.